How did we get to the point where we would work 8-10 hours a day for flimsy rectangles of plastic? When you stop to think about, the value of the money you’re paid isn’t in its physical worth. It’s in its theoretical value.

A common statement you hear is “money has value because we agree it does.” But how did we collectively come to this decision? Because on the face of it, it doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Why is my worthless paper (or polymer as some notes are today)worth the same as the car you’re selling that I’ll drive for another 10 years? Or the food I eat in order to stay alive?

Without the shift from hard currency like gold and silver, we couldn’t have the massive global economies we have today. It has impacted every aspect of society; from the financing of governments to making Square payments on your phone at a car boot sale.

By understanding the journey we’ve come on and how we’ve come to think about money, we can get a better handle on understanding how bits and data can be seen as money in the future.

The Story of Money

Trade

The origins of money are found in trade, as you might expect. In fact, there is evidence that, before humans even had settled societies, or shops to buy things in, we would trade things with each other. This could be things we made, or things we foraged or hunted. Trade allowed early humans to pool resources, and share access to things not easily available, such as fruits or fish.

When we did settle down and build civilisations, we see trade really take off. When we started to cultivate the land and establish shared means of existence, we were able to specialise. And when you specialise, trade becomes necessary to the running of society. That way tomato growers get their pottery and potters have soup to put in their bowls.

The problem with direct trade is that sometimes you need something, but the person who has it doesn’t want it from you. This problem is known as the coincidence of wants.

Coincidence of wants

Let’s say you grow oranges and I’m a hunter. If you need meat and I need some vitamin C in my diet, perfect! We can trade. But what happens if you go vegetarian, but I still want oranges? I can’t trade with you directly.

But maybe I could find some third good you need and trade my meat for it. But down that road, madness lies. The third person might want something from someone who wants something else and maybe the only person who needs a delicious steak is the 10th person in that chain.

By the time I’ve done all that, I’m going to be really tired and will have lost so much time in trading that I could have spent hunting.

This problem only gets worse when you think about the lack of storage options available to ancient peoples. I can’t just freeze the meat I get from hunting and store it to trade until the oranges ripen and the harvest comes in.

Money: The trade good everyone wants

But what if there was some third good that we all wanted, that everyone agrees has value? This is where money comes in.

Money is just a third good that can be used conveniently that we all agree has value. It is a good that acts as an intermediary, with which all other goods, from meat to oranges to hats, can be traded.

So long as its durable and hard to create or obtain, almost anything can be money. With those being the only stipulations, people have gotten pretty creative with what they agree money to be.

5 Weirdest Things Ever Used As Money

5. Shells

In Langa Langa Lagoon, in the Solomon Islands, archaeologists discovered evidence that shell money could have been in use as early as 1200 B.C., and it’s still in use today. This makes it the oldest form of money in existence.

The shells are often used to create jewellery pieces that are traded, used as peace offerings, or offered during bridal ceremonies. Since the shells have become increasingly rare over time, their value has also increased. Today, one string of cowries is worth 1,000 Solomon dollars, which is about £95.00

4. Knives

In ancient China, tools and knives were used as money. These bronze cast currencies represent one of the first forms of precious metal money. While the stories of how these became money are uncertain, the evidence is clear.

In fact, the tradition of having a hole in your money, which persisted in china until the 20th century is thought by some to originate in the ancient spade money.

3. Beer Bottle Caps

Beer bottle caps were used as currency in parts of Cameroon, which was in the grips of a promotion frenzy by rival breweries in 2005. Intense competition between beer companies saw 20 million bottles given away, some of which contained a prize.

Given the convenience and proliferation of the bottle tops, people started using their winning bottle tops to pay for taxi rides. The prizes, which were revealed beneath the bottle top, included mobile phones, luxury cars and of course more beer.

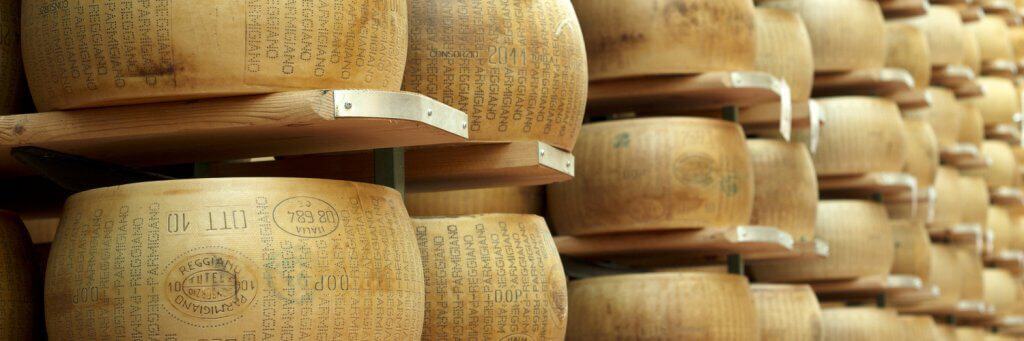

2. Cheese

In 1953, the Credito Emiliano bank in Italy started accepting Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese as collateral for loans as a way of supporting cheese-makers during the recessions. Valued at €300 per wheel, each cheese has a serial number so that it can be traced if it is ever stolen.

Using your cheese, the bank allows loans for as long as 34 months, which is equal to the approximate time it takes for the cheese to age.

The system was so successful that it persists to this day. Today, the bank’s warehouses are said to hold as much as 17,000 tons of the cheese, which is valued at around £140 million in total.

1. Massive Stone Wheels

On the island of Yap in the Pacific Ocean, they use huge limestone rings as currency. These huge doughnut-shaped pieces of rock were transported to the island of Yap by canoe to be used as currency. The value of the stones was kept high due to the difficulty and hazards involved in obtaining them.

To quarry the stones, Yapese adventurers had to sail to distant islands and deal with local inhabitants who were sometimes hostile. Once quarried, the disks had to be transported back to Yap on rafts towed behind sail-driven canoes. The scarcity of the disks, and the effort and peril required to get them, made them valuable to the Yapese.

The best part about your currency being a massive rock is that it’s really hard to lose. In fact, one story goes that while bringing back one stone, a storm hit and the stone sank to the bottom of the sea.

When the survivors got back to Yap and explained what happened, everyone agreed it still counted even though no one had ever seen it. To this day, someone still owns, and trades with, that massive undersea rock.

Commodity Money

The scarcity of ancient money is essential to retaining its value, but so is its inherent worth. Old fashioned coins made from gold and silver were considered valuable because gold and silver itself is valuable. Gold is rare, valuable and useful. These qualities make it easy for people to trust in the worth, and thus the wealth, of gold. This type of money is known as commodity money, because the money itself is a commodity. In this way, money is just another trade good, a means for which goods are exchanged.

However, there are a number of problems with commodity money the larger an economy grows. Firstly, gold is really heavy and difficult to move around. If you’re doing deals involving massive sums of money, like our global economy demands, gold becomes burdensome. If you’re having to transfer it through dangerous places, gold becomes risky too.

Another problem with commodity money is that it has a ceiling. Gold and silver is rare, which is why it’s valuable. But, that scarcity means that ultimately there is a cap on how much trade you can do. If your economy grows to the point where the need for gold exceeds the amount you have, inflation starts to occur.

On the opposite scale, commodities whose value is based on scarcity are subject to change when more is found. For example, in the 15th century, when Spanish colonists discovered silver in Central America, the influx flooded the market and inflation ran rampant as the value of existing silver began to decrease.

Gold and silver can also be debased. This happens when someone re-mints coins to include parts of other gold-ish metals and passes them off as being the same value. By doing this, you create a situation where the value of gold, and thus people’s trust in it as a currency, begins to erode.

But people’s trust in gold proved extremely difficult to shake off. It took almost a hundred years of economic theory and experimentation to convince people to give up their gold coins in favour of something that, on the face of it, has no value whatsoever.

IOUs: The Early Paper Money

The idea of using paper for money comes to us from China, via the travels of Marco Polo. Essentially it was a means of using IOUs in lieu of cash when conducting large transactions. 7th Century China used a coinage system that started to become unwieldy as its economy grew.

Merchants found themselves needing tens of thousands of coins to complete transactions that were so heavy as to prove impractical for day to day business. In response to this, the Chinese government started issuing pieces of paper with the amount of coins written on them, which people could exchange for the real thing at the capital at any time.

When these slips of paper were issued, merchants who sold things to the government found that the paper was more useful than the coins. They started buying their own things with the government’s IOUs and a slip could change hands multiple times before anyone went to the capital to cash it in. By the 11th Century, paper money caught on and the Government itself started printing its own promissory notes.

Once the idea established itself, lots of people tried to introduce paper money to varying degrees of success. A corrupt Iranian regime tried to introduce paper money after all the gold in the treasury was spent. Backed by nothing at all, the economy collapsed at the first sign of pressure. This happened anywhere where people sought to exploit the idea of paper money to their advantage.

The Rise Of Banking

Renaissance Italy was the place the idea of paper money really starts to take route in the form of IOUs, or promissory notes. Merchants would buy goods with IOUs representing their local bank.

The seller could pick up their gold from a regional branch of the merchant’s local bank in exchange for the promissory note. The note would then be taken back to the merchant’s local bank, who would later collect from the merchant.

But people saw the benefits of paper money and soon the notes were floating around in the market, being traded among other merchants on a regular basis without being cashed. Over the years, this idea began to evolve. By the 1600s, banks in England started issuing receipts for gold in various denominations that anyone could cash, and thus, the bank note was born.

Bank notes were great for banks. As long as the bank notes remained in circulation, the banks were free to use the money in the bank those notes represented. Fractional reserve banking policy allowed them to play with more money than they actually had.

People trusted that they could go back to the bank and collect the gold at any time, and the banks trusted that not everyone would at once. As long has this balance held, everyone was happy. But of course, that wasn’t what happened.

As soon as people realised, or simply felt like there were more notes out there than there was gold, people started demanding the gold promised by the bank notes. In Sweden, France and England, this happened over and over, both at the local and state level. The reason for this is because people still believed in gold, not in money.

Gold Has No Value

It wasn’t until 1690 that the fundamental idea of money was changed. Economists, including the excellently named Nicholas Unless-Jesus-Christ-Had-Died-For-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned Barebone (a.k.a Nicolas Barbon), started to posit a new idea: That gold and silver only have value because we agree they do.

This was also a time when we started to change the way thought about spending money. By the 1700s, the bond between morality and spending was beginning to wane. Up until then, most of the writing about money was done by the church, who naturally encouraged thrifty lives of meagre living.

But, as fractional reserve banking and the invention of the mortgage gave people greater access to money, people were encouraged to spend money on fashion, innovations and other indulgences that help drive a dynamic economy. This idea led to Adam Smith’s groundbreaking theory of supply and demand.

Without being tied to the value of commodity money, the wealth of nations was no longer capped by the physical bullion it can store. You didn’t need stockpiles of gold in your vaults to be wealthy any more.

This idea was radical because it divorces money (the physical mechanism of exchange) from any intrinsic value. Money’s value, it was argued, should be principally symbolic and that its main function is to simply enable trade. Money had to be the means by which goods are exchanged, rather than for which they are exchanged.

Getting Off The Gold Standard

Despite these advances, banks still backed paper money by gold well into the Twentieth Century. In a world where nations were popping up and vanishing again, regimes rising and falling, gold remained the one immutable constant that governments could rely on.

But for many countries, getting off the gold standard wasn’t an option, but a necessity. The cost of two World Wars devastated the global economy. Prosecuting war completely drained the gold reserves of nations fighting on both sides of the conflicts. In order to get their hands on the munitions and hardware they needed to fight the Nazis during the Second World War, the allies turned to America for help.

At the time, America had a better infrastructure and greater natural resources than any other nation on earth. By the time the war ended, America controlled two thirds of the world’s gold as a result of its economic might. During the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, the International Monetary Fund was established.

Other countries would back their currency not with gold, but by the American dollar. In this way, countries could cash in any amount of their domestic notes in exchange for US dollars.

The US dollar remained backed by gold until 1971. America’s gold reserves were falling, as nations began redeeming their dollars for gold. As a result, the value of the dollar began to fall. President Nixon blamed the drop in the dollar on “foreign price-gougers” and got the public support he needed in order to finally take the dollar off the gold standard.

Politically, Nixon’s actions were a great success. The Dow rose 33 points the next day, its biggest daily gain ever at that point, and the New York Times editorial read, “We unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved.”

Now off the gold standard, the US dollar and every currency still tied to it, including the pound and Swiss Franc, was left to float, backed by nothing but the agreement that it has value. Finally, in the second half of the Twentieth Century, money became the means by which goods were exchanged, rather than for which goods are exchanged.

Tomorrow’s Money

Today, our money has value because we agree it does. We agree so much that it is regulated and managed by the government. If all we need to do is agree that something has value in order for it to be money, anything can be money!

In 2009, the first decentralised cryptocurrency appeared. Called bitcoin, this digital financial instrument uses strong cryptography to secure financial transactions, control the creation of more units, and verify the transfer of assets.

Being decentralised, no one body controls the books of cryptocurrency. Instead, bitcoin works through distributed ledger technology, usually a blockchain, that acts as a public financial transaction database.

Cryptocurrencies are attractive because of their decentralised nature. Unlike other forms of currency, you can’t tamper with it. Centralised currencies are controlled by banks or governments, who can manipulate the creation, and thus the value, of the currency.

The idea of cryptocurrencies is that they are a financial instrument that is free from the machinations of “the establishment”. They are also very hard for law enforcement to seize, making them equally attractive to criminals.

The theory behind cryptocurrencies is sound. It is a secure and stable currency that cannot be tampered with. The problem is that not everyone agrees that cryptocurrencies are safe. Until we all feel confident in cryptocurrencies and they settle down to become a part of life, they remain at the mercy of market speculation.

The bubble could burst and anyone investing in them could lose. But if it doesn’t, those who bought into bitcoin early will become very rich indeed.

However, a cashless economy isn’t coming any time soon. As long as people remain indecisive about bitcoin and suspicious of banks, the 500 billion banknotes in circulation will continue to be used with confidence all over the world.